|

One bonus of conducting interviews over Zoom in the COVID-19 era is that Zoom will auto-generate a transcript of the interview. This is a huge timesaver because there are few things as tedious as manually transcribing an hour-plus long interview (multiplied by anywhere from 20 to 100--the typical number of interviews conducted for a single project). It's a lot. So when I found out about Zoom's free transcription service, I was very excited.

I have found that the quality of Zoom's transcripts is pretty good. Of course, they will still require some manual editing, depending on how much jargon is used, whether there is background noise, etc. One of the biggest drawbacks to the Zoom transcripts has been, in my experience, the atrocious formatting. The formatting produces extremely long documents that are hard to read. After downloading my first Zoom transcript, I began to manually reformat it and quickly realized that any time saved by the auto-transcription would be wasted by manual reformatting. So I wrote a program to do the reformatting for me. The program, which you can download here, is written for R. I have made it as user-friendly as possible. All you have to do is change a few lines of the code (to specify the working directory, the filename, and the participant name) and the rest you can leave untouched. You will find instructions within the file. I hope this can save us interview researchers some collective time! Last week I drove out to Milwaukee from Ann Arbor for a week-long archive expedition. I had already been in contact with archivists and librarians at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Archives and the archives at the Milwaukee Public Library. This wonderful, searchable database of Wisconsin finding aides was a tremendous help in putting together a precise list of collections, boxes, and specific folders I wanted to consult. Having sent these lists to the two archives ahead of time, they were able to have the boxes ready and waiting for me so I could maximize my reviewing time. In preparation for my trip, I did a fair amount of research on the new technologies available to archive researchers since the last time I did archive research a decade ago. Back in 2010-2011 I did archive research at a handful of archives in Mexico City using a point-and-shoot camera digital camera. In the archives that did not allow photographs, I took notes on a laptop and even copied word-for-word entire documents. Luckily, both the UW-M and the MPL archives allow non-flash photography. I'm sharing some tips of how I made the process work for me (and some lessons learned for next time) in hopes that this is helpful for other researchers. Digitalization with Microsoft Lens app To create digital scans of documents, I elected to use the Microsoft Lens app on my iPhone. I get free institutional access to the Microsoft Office suite, so I'm not sure if this app has a cost for non-affiliated users. Here's how I used the app:

Equipment to bring with you to the archive In addition to bringing your phone (and water and snacks!), there are also a few pieces of equipment that I found essential or that wish I had brought with me.

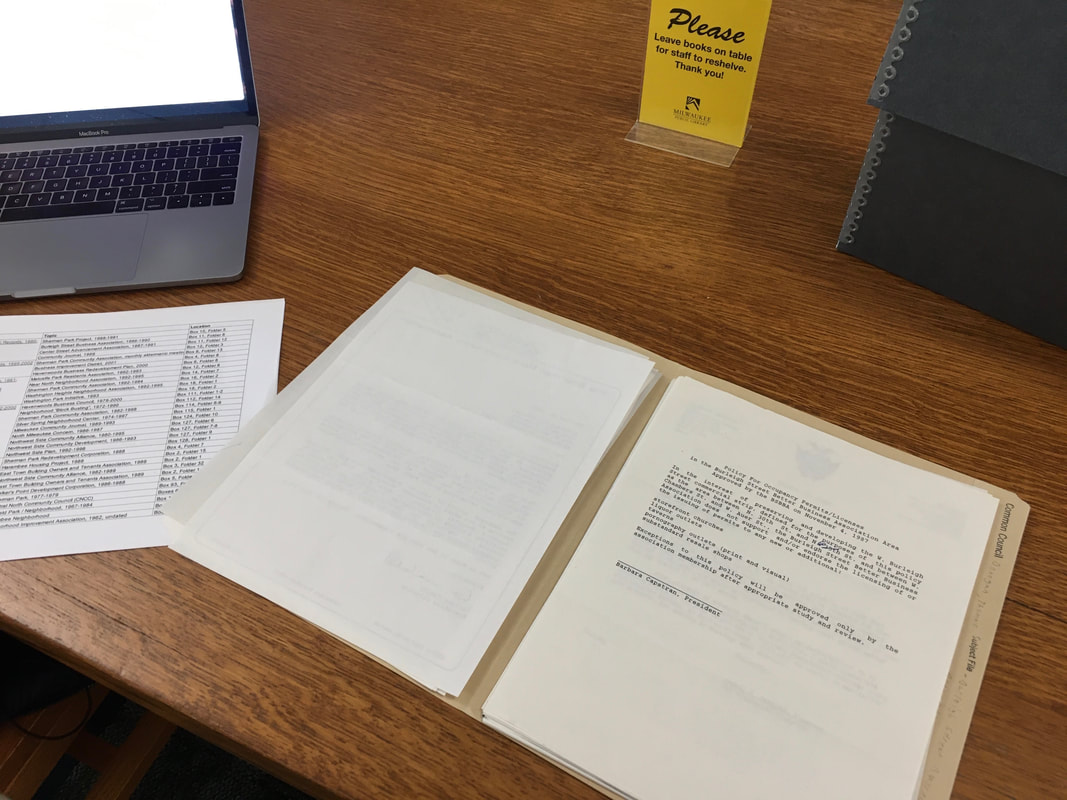

My set-up at the Milwaukee Public Library archive. To the left, the list of individual collections, boxes, and folders that I planned to consult.

Mexico City's "megacorte" (mega shutoff) of water begins today. I haven't seen or heard much news coverage in English, but it is truly a mind-boggling event. One of the major water provision systems in Mexico City, which supplies water to around 8 million residents in the metropolitan area, was shut off this morning and won't be turned back on until November 4, or possibly as late as November 8. The shutoff will allow for critical repairs. Imagine 8 million people not having running water to bathe, wash dishes, flush toilets, etc. for a week. For those who are fortunate to have never lived without household running water (like me, until living in Mexico City), you really don't realize how much of daily life relies on easy access until you no longer have it.

Mexico City has a major water problem and residents are used to having to endure days or weeks without water. Obviously, some neighborhoods deal with this more frequently than others and, not surprisingly, this unequal access to water maps onto socio-economic class in the city. Even in my upper-middle class neighborhood in Mexico City, Narvarte, we would usually experience 2-3 shutoffs per year that could last a few days or even over a week. This shutoff, however, is the largest in Mexico City's history and is being described by residents in apocalyptic terms. Interestingly, this megacorte has coincided with the escalation of a heated debate over infrastructure in the city that culminated with a national vote over whether or not to continue with plans for a new airport in Mexico City. The vote, which took place over the weekend, decided against the airport and the President-elect, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, announced his plans yesterday to cancel the project once he enters office in December. The planned airport would have been constructed on the mostly drained bed of Lake Texcoco on the eastern edge of the metropolitan area (not far from the current airport). Activists opposing the airport framed their fight as one in defense of water/nature and indigenous rights. The hash tag #YoPrefieroElLago ("I prefer the lake") was widely used to mobilize the vote against the airport. Sarah // Madison, WI I awoke, drowsy from the dramamine, and for a moment I forgot where I was. Looking out of the window of the bus, as it wound along a narrow, curving road, I saw nothing. Soft white nothingness. From time to time images appeared out of the dense white fog: a tree, a storefront. The bus slowed to a stop: we had arrived in Chapulhuacán, Hidalgo. Chapulhuacán is a small town in the northern, mountainous region of Hidalgo. While it is not far from other, larger cities in the region, it feels very removed. The winding, poorly kept road that leads in and out of the town makes travel slow, arduous, and nauseating. We had traveled over 8 hours from Mexico City. Chapulhuacán is uniquely situated in the heart of a region that sends thousands of workers to the U.S. each year to work on temporary employment visas. That is why we were there--to meet with worker leaders in the region, organize a few workshops, and promote Contratados. On our last day in Chapulhuacán, the fog cleared. Deep, rich green replaced the gray-white. The landscape took my breath away. Coffee is a major source of income in the region. Most residents grow coffee for themselves, and many maintain plots large enough to sell as well. Sarah // Mexico City, Mexico

I admit it: I have been always been a little obsessed with public radio. My parents always had the local public radio station on in the car, but I first got hooked on This American Life my freshman year of high school. I also listened to other programs, including LatinoUSA with María Hinojosa. It became a dream of mine to be on a public radio show. On January 9, 2014, my dream sort of came true: I was interviewed about Contratados for LatinoUSA. It feels a little anti-climatic, but it none the less happened. The segment was part of a show called "The More You Know." Sarah // Mexico City, Mexico

A week ago, I was invited to speak on Entrecruzamientos, a program of Radio Educación, about access to information and labor recruitment. The interview was organized by Fundar and Gedisa, who coordinated and published Migrar en las Americas, as part of the book promotion campaign. You can listen to the interview online here. In the interview, I spoke about the vulnerability that labor recruitment imposes--not only on migrant workers, but also on families and entire communities. This is a perspective that I think deserves a much deeper examination. I also spoke about solutions, and proposed that migrant workers have to create their own solutions and become their own advocates. Migrant workers cannot expect that governments, employers/recruiters or even advocates will effectively ensure the protection of their rights--they have to organize and become their own advocates. The more that I delve into the issue of labor recruitment, the more that I feel this is true. The interests of capital (which are opposed to those of migrant workers) will always be more important to the government than the interests of migrant workers. This means that any policy or program implemented by the government to supposedly improve protections for workers will never truly do so. No state-provided solution will ever undermine the interests of capital in any real way. This leaves workers to organize and create their own solutions--independent of the state. Contratados.org is a good start. Also, here is a picture of me with Migrar en las Américas, where my co-authored chapter appears, for sale at the Fondo de Cultura Económica. Sarah // Mexico City, Mexico

Article abstractThe hiring of Mexican workers for temporary employment in the United States is a transnational process with little transparency and accountability in which thousands of Mexicans have suffered from fraud and abuse. The program structure, controlled by employers, allows and encourages the use of agents and subcontractors and lacks the mechanisms to protect potential migrants. The nearly complete lack of public and accessible information encourages the violation of migrants’ rights. This article (1) presents an analysis of how the H-2A and H-2B programs work, (2) explains the legal and regulatory frameworks of the programs, (3) explores current problems in access to public information about recruitment, (4) explains the work that CDM has done to access public information through the Federal Institute of Access to Information and Data Protection (IFAI, the acronym in Spanish) in Mexico and the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in the United States, (5) argues that both governments must guarantee free and timely access to public information for migrants so they may protect themselves from fraud and abuse, and (6) proposes a series of changes to transparency laws so that they meet the needs of migrant workers. Key words: Labor recruitment; temporary work; H-2A visa; H-2B visa; migrant workers; labor rights violations; right to access public information; Freedom of Information Act (FOIA); Instituto Federal de Acceso a la Información y Protección de Datos (IFAI) The following is a summary of my remarks during the presentation of Migrar en las Américas on July 24, 2014, in the Museo de las Culturals Populares in Mexico City, Mexico.

|

archives

January 2022

categories

All

disclaimerThe views expressed in this blog and on this website are my own.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed